CNN, Walter Duranty is Not a Good Role Model

![]()

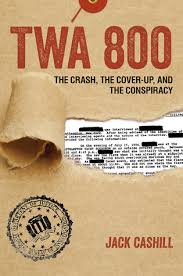

Order Jack Cashill's latest book, TWA 800: The Crash, the Cover-Up, and the Conspiracy

![]()

About Silenced: Flight 800

and the Subversion

of Justice (DVD) -

-Buy the Silenced DVD-

![]()

© Jack Cashill

February 14, 2018 - WND.com

More than a few people in the media this week compared CNN’s fawning Olympic coverage of Kim Yo Jong, the sister of North Korean despot Kim Jong Un, to the work of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Timesman Walter Duranty.

These comparisons were not meant as a compliment. To understand why we might want to flash back to the month of November 1933, the most thrilling in Duranty’s professional life.

The one-legged, British-born, American citizen had just arrived in Washington D.C. from Moscow. He had come these many miles to witness President Roosevelt officially recognize the Soviet Union.

Everyone knew that were it not for Duranty’s reporting the president would never have pushed for recognition. A little more than a year later, Simon & Schuster published Duranty’s take on the Soviet experiment. The title of the book was the scarily appropriate, I Write As I Please.

In this classic of willful blindness, the presumably objective journalist sheds his usual cynicism only to show his affection for Comrade Stalin.

As Duranty relates, he “felt as pleased as punch” when Stalin had announced the Five-Year Plan in the fall of 1928. Stalin, after all, was the world’s “greatest living statesman.”

As part of the plan, wrote Duranty, Stalin was prepared “to socialize, virtually overnight, a hundred million of the stubbornest and most ignorant peasants in the world.”

As the Black Book of Communism notes, “Recent research in the newly accessible archives has confirmed that the forced collectivization of the countryside was in effect a war declared by the Soviet state on a nation of smallholders.”

The war was brutal. In 1930 alone, some 2.5 million peasants participated in the 14,000 revolts or riots that engulfed the countryside. Somehow, this all seems to have escaped the attention of Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty. Much worse would escape him in the years ahead.

By the end of 1930, 700,000 people had been shipped to the nether regions of the Soviet Union. By the end of 1931, that number had swollen to 1.8 million.

By stripping the countryside of its more productive citizens and reducing the rest to penury, Stalin had set the stage for the horror show that was to follow.

He and his cohorts began by shaking down those left on the land for a bigger slice of the action.

In 1932, for instance, the government take was to be 32 percent higher than the year before. By that year, the peasantry was faced with a grim choice: resist the collection or starve to death. They resisted.

Stalin sent in his shock troops. They had come to enforce the infamous 1932 “ear law,” so dubbed because an individual could and would be arrested for withholding any “socialist property” right down to an ear of corn.

By late summer 1932, when even hard-liners began to plea for some relief for these peasants, Moscow turned them down cold. This hardheartedness gave birth to the adage, “Moscow does not believe in tears.”

Harassed and starving, millions fled these rich agricultural lands for the cities. At this point, Stalin got serious. In December 1932, in order to “liquidate social parasitism,” he mandated the equivalent of passports for all internal migration.

In January 1933, Molotov and Stalin instructed local authorities and the GPU to stop the peasants from leaving their farms “by all means necessary.” These “means” included mass execution. In February 1933 alone, the secret police reported that it had stopped more than 219,000 desperate peasants in their tracks.

Duranty knew the score. He told fellow reporter Eugene Lyons and others that he estimated the victims of the terror-famine at around seven million, but he proved as indifferent to humanity as he was to the truth.

His callousness rivaled Stalin’s own. “Russians may be hungry and short of clothes and comfort,” Duranty wrote in the New York Times in 1932. “But you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”

Duranty had his own reasons for suppressing the truth. As the British Foreign Office openly discussed, he was angling for U.S. recognition of the Soviet Union.

One dispatch bluntly noted that such recognition “would greatly enhance his reputation in the Soviet Union and give him a cheap triumph in the United States.” And cheap triumph is exactly what he got.

“The ‘famine’ is mostly bunk,” Duranty wrote to a friend in June 1933. He used his and the Times’ authority to feed the story to a progressive establishment that had developed a taste for just such bunk.

The Pulitzer Committee awarded him its top prize for news correspondence in 1932. The Committee cited the “scholarship, profundity, impartiality, sound judgment, and exceptional clarity” of his reporting on the Five-Year Plan in the Soviet Union.

They have been rewarding each other for fake news ever since.