Manti Te’o Meet Margaret Mead

Get your copy of Deconstructing Obama

___

Jack Cashill's book:

Hoodwinked: How Intellectual Hucksters have Hijacked American Culture

Click here for signed first edition

©Jack Cashill

WND.com - 14, 2013

In the last few weeks, the media have scrutinized Notre Dame All-American linebacker Manti Te’o’s imaginary girlfriends more thoroughly than they have the very real terrorists who killed four Americans in Benghazi.

To those who care, the question that remains is whether Te’o conspired to fabricate his seemingly tragic relationship with imaginary girlfriend Lennay Kekua or whether he is a victim of a cruel hoax.

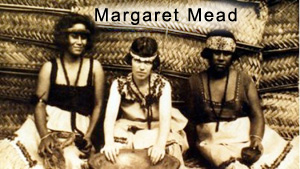

If he has been hoaxed, Te’o will not be the first victim of traditional Polynesian trickery, nor the most consequential. That latter honor belongs to culture-changing anthropologist Margaret Mead.

If he has been hoaxed, Te’o will not be the first victim of traditional Polynesian trickery, nor the most consequential. That latter honor belongs to culture-changing anthropologist Margaret Mead.

“What we do know is that in every Polynesian community there is the waha nui,” wrote Hawaiian historian Herb Kawainui Kane to a mutual friend in an email, “the self-appointed spokesman and tale teller, who has a talent for anticipating what a visitor wants to hear and can invent a story on the spot.”

Unfortunately, Herb Kawainui Kane is no longer around to shed light on the Te’o case. The celebrated author died two years ago at 82.

But he had a good deal to say about Mead, the “youth with romantic ideas,” who “found the information she was looking for in Samoa.” The reason she found it? Teenage girls “had invented tales to suit their visitor.”

In the fall of 1922, Mead took a course from Franz Boas, her mentor at Columbia University and the godfather of modern anthropology. Boas taught that “social conditioning” was responsible for the complete molding of the individual, and Mead believed what Boas preached.

When just 24, Mead accepted a grant to travel to Samoa. In the process, she hoped to put her own omnivorous sexual appetite in a more favorable context.

Although married at the time, Mead was about to enter “an intimate Sapphic relationship” with Ruth Benedict, Boaz’s teaching assistant and America’s other famous female anthropologist.

Although married at the time, Mead was about to enter “an intimate Sapphic relationship” with Ruth Benedict, Boaz’s teaching assistant and America’s other famous female anthropologist.

Once in Samoa, the flighty young Mead dithered aimlessly for months before starting her fieldwork. Finally, with a few weeks left on her grant, she started traveling around the islands with two teenage girls and questioned them eagerly about their sex lives.

The girls had no idea what Mead was up to. They didn’t know she was an anthropologist or what one even was. But in the waha nui spirit, they proceeded to spin the kind of “recreational lies” that Mead wanted to hear.

Pinching each other all the way, the girls filled Mead’s head with wild tales of nocturnal liaisons under the palm trees.

“She must have taken it seriously,” one of the girls would confess years later, “but I was only joking. As you know, Samoan girls are terrific liars when it comes to joking.”

Back in New York, Mead banged out a report that quickly became the book Coming of Age in Samoa. According to Mead, Samoan girls often embarked on several sexual adventures each night. And why not? “The concept of celibacy is absolutely meaningless to them.”

Given “the scarcity of taboos” homosexuality was common and masturbation was universal. Illegitimate children were welcome. Prostitution was harmless. And divorce was simple and informal.

This casual familiarity with sex, argued Mead, led to a culture in which “there are no neurotic pictures, no frigidity, no impotence, except for the temporary result of severe illness, and the capacity for intercourse only once in a night is counted as senility.” And all this pre-Viagra!

Better still, Samoan-style openness dissolved the proprietary tensions—“monogamy, exclusiveness, jealousy, and undeviating fidelity”—so problematic in a possessive American culture.

Best of all, Mead discovered that the difference between Samoans and Americans had nothing to do with biology and everything to do with culture, just as Boas predicted. How about that?

“What accounts for the presence of storm and stress in American adolescents?” asks Mead. The answer was simple enough: “the social environment.”

The New York Times, as foolish then and now, described the book as “unbiased in its judgment, richly readable in its style . . . a remarkable contribution to our knowledge of humanity.”

The book quickly became a staple in the progressive canon. At the time of Mead’s death fifty years later, Coming of Age in Samoa was still selling 100,000 copies a year and was widely considered a “scientific classic.”

In fact, the Times editors and their fellow travelers in academia had willfully bought into the greatest scientific hoax since the Piltdown Man. A handful of honest anthropologists would later admit, as Kane did, that Mead’s take on Samoan sexual practices was “comprehensively in error.”

In reality, at the time of Mead’s visit, every attempt was made to safeguard the virginity of Samoan girls. The almost complete Christian overlay on Samoan culture only reinforced the traditional premium on chastity. There was much at stake.

At marriage, the bride had to undergo a formal virginity test, and it was not multiple-choice. The results mattered. There was nothing casual about it. The groom-to-be staked his pride and honor on the outcome.

When a few intrepid anthropologists tried to correct the record, no one wanted to hear them. For a variety of obvious reasons, academia and the media obviously liked what Mead had to say.

Britannica concise was the rare encyclopedia to admit there was any controversy at all, conceding that later anthropologists questioned “both the accuracy of her observations and the soundness of her conclusions.”

But in the very next sentence, the reader learns that Mead became “a prominent voice” on issues like women’s rights and nuclear proliferation, and that her great fame owed as much to this as “to the quality of her scientific work.”

A few years from now, Manti Te’o will be the answer to a trivia question, but our sons and daughters will still be obliged to read Mead’s nonsense about a sexual paradise no more real than Te’o’s girlfriend.

Webmaster's Note: Jack Cashill's Book-TV presentation of "Deconstructing Obama" can be viewed at http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/298382-1

Editor's note: For a more complete account of this phenomenon, read Jack Cashill's amazing book, "Hoodwinked: How Intellectual Hucksters Have Hijacked American Culture.