The Improvised Odyssey of Barack Obama

(expanded version)

Jack Cashill's book:

Hoodwinked: How Intellectual Hucksters have Hijacked American Culture

Click here for signed first edition

©Jack Cashill

AmericanThinker.com - December 28, 2008

There is no science to validate the thesis that follows, no academy to adjudicate it, and little hope of convincing the Obama faithful even to consider it, let alone concede its validity. That much said, the evidence is self-evident, accessible to all, and overwhelming.

The thesis is simple enough: Bill Ayers served as Barack Obama’s muse in the creation of Obama’s 1995 memoir, Dreams From My Father. Ayers breathed creative life into this ungifted amateur, who had written nothing of note before, and nothing since, and reconceived him as a literary prodigy.

“I was astonished by his ability to write, to think, to reflect, to learn and turn a good phrase,” said Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison of the Dreams’ author. “I was very impressed. This was not a normal political biography.” Agreed, it was not normal at all.

For simplicity’s sake, I refer to the author of Dreams as “Obama.” He provided the basic narrative and surely had the final say. Not content to merely edit, however, the highly skilled Ayers appears to have woven the rough strands of Obama’s life with tales from Homer’s Odyssey and to have spun a work of literature in the process.

In his thoughtful 2008 essay, “Narrative Push/Narrative Pull,” Ayers almost seems to be describing the muse’s role in the creation of Dreams, perhaps even taking credit for it. “The hallmark of writing in the first person is intimacy,” Ayers writes. That much said, by fusing Obama’s story with Homer’s, Ayers creates something like the “monomyth” as famously delineated by Joseph Campbell. “The universal is revealed through the specific, the general through the particular,” Ayers adds.

Obama reaches the very same understanding in Dreams. “And so what was a more interior, intimate effort on my part, to understand this struggle and to find my place in it,” he writes, “has converged with a broader public debate.”

The muse leaves scarcely an Homeric trope unturned in his mining of the Odyssey to describe Obama’s “personal interior journey.” Before he completes his heroic cycle, Obama will confront green-eyed seductresses, blind seers, lotus-eaters, the “ghosts” of the underworld, whirlpools, and about a half dozen sundry “demons.” It was not, however, until I identified a menacing one-eyed bald man in Dreams that I became convinced that the parallelism was conscious.

Early in his own 2001 memoir, Fugitive Days, Ayers tips his Homeric hand. “Memory sails out upon a murky sea—wine-dark, opaque, unfathomable,” he writes with a knowing wink. “Wine-dark” is quintessential Homer. Best-selling author Thomas Cahill named his book on ancient Greece, Sailing the Wine-Dark Sea. It did not surprise me to learn that Cahill had attended my high school, but then again so had Weather Underground member, Brian Flanagan, who took the same Greek courses I did. Ayers and pals may have been lunatics, but they were literate ones.

Dreams and the Odyssey both begin in media res, a literary technique in which the narrative starts in mid-story and not from the literal beginning. Odysseus’s son, Telemachus, is twenty when the Odyssey begins. Obama, now in New York, tells the reader he has just turned twenty-one at the outset of Dreams.

More intriguing, each begins with the young protagonist receiving an unexpected call that inspires him to seek out his missing father. The goddess Athena, in disguise, gives Telemachus the word. In Dreams, it is Obama’s Aunt Jane from Nairobi. Odysseus had quit the isle of Ithaca and abandoned his son to fight in the Trojan War when Telemachus was a month old. Obama’s father quit the isle of Hawaii and abandoned his son for Harvard when Obama was two.

It is only after his aunt calls to tell Obama that his father has been killed in a car accident that he begins his journey of discovery in earnest. On this journey, he assumes the role of both Telemachus and Odysseus, the son seeking the father, and the father seeking home.

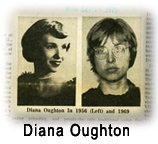

Ayers, by the way, so liked the dramatic structure of the Dreams’ opening  sequence that he repeated it in Fugitive Days, which also opens in media res with a dramatic phone call. Ayers learns that the woman he then loved, Diana Oughton, had been killed in a Greenwich Village bomb blast. Like Obama, he has a hard time understanding what he is hearing. He drops the line in shock, and the conversation ends abruptly just as it does in Dreams.

sequence that he repeated it in Fugitive Days, which also opens in media res with a dramatic phone call. Ayers learns that the woman he then loved, Diana Oughton, had been killed in a Greenwich Village bomb blast. Like Obama, he has a hard time understanding what he is hearing. He drops the line in shock, and the conversation ends abruptly just as it does in Dreams.

A serious student of literature— Hyde Park neighbor Rashid Khalidi gives Ayers major credit for helping with his book, Resurrecting Empire—Ayers has a particular interest in the art of the memoir. “T he reader must actually see the struggle,” he writes. “It’s a journey, not by a tourist, but by a pilgrim.”

As a former merchant seaman, Ayers often thought in terms of charts and maps when plotting life’s journey. In Fugitive Days, he yearns for a “mariner's chart of the past” to help navigate, but he knows there is no such thing. He and his colleagues must face every day “ as free people with neither road maps nor guarantees.”

Obama uses the imagery of maps and charts much as Ayers does. In the introduction of Dreams, Obama talks of the book he had originally intended to write, a prosaic analysis of race and law. He describes it as “an intellectual journey that I imagined for myself, complete with maps and restpoints and a strict itinerary.” He changed his mind, of course, and settled on “a record of a personal, interior journey--a boy’s search for his father, and through that search a workable meaning for his life as a black American.” Like Ayers, Obama sees this personal “journey” as a “pilgrimage.”

As Obama becomes aware of his blackness, he begins “to see a new map of the world, one that was frightening in its simplicity, suffocating in its implications.” He traces the map’s origins back to the day, centuries earlier, when “blind hunger” drove the white man to land on Africa’s shores. Ayers, by the way, uses the word “suffocating” four times in Fugitive Days.

“That first encounter had redrawn the map of black life,” Obama argues, “recentered its universe, created the very idea of escape.” At this stage of his life certainly, Obama sees the universe in naturalistic terms as a cruel and godless place. No amount of good works had “the power to change its blind, mindless course.”

An amoral blindness deforms the world of Fugitive Days as well. Ayers writes of the “blinding myth” of progress, the “willed blindness” of suburban America, the sadness of “those who are perpetually blind to the cruel side of the world.”

“We imagine a world,” Ayers writes, “we create a reality, we bracket a piece of experience, and it becomes acute, hyperreal, dazzling, revealing, enabling, and also blinding, perhaps deadly.” He fears that if he yields to inaction, he too will be “moving along blindly” like the rest of humanity.

“I was operating mainly on impulse,” Obama says of his life before being called to action, “like a salmon swimming blindly upstream toward the site of his own conception.”

Swimming imagery courses through Dreams and Fugitive Days as freely as “blind” imagery. In Fugitive Days, Ayers relates that he and his radical pals were “swimming silently in the sea of the people.” This became a common theme among them. They saw themselves as “fish in the sea,” finding anonymity in faceless crowds.

If Ayers swam comfortably in his metaphoric water, Obama did not. Later, an African aunt will caution him, “If one is a fish, one does not try to fly-one swims with other fish.” But at the stage of his life, Obama is neither fish nor fowl, and he knows it. He swims blindly through a blind universe without a clear sense of who he is.

The crafty Ayers writes about the sea almost as knowingly as Homer. “I’d thought that when I signed on [as a merchant seaman] that I might write an American novel about a young man at sea,” says Ayers in Fugitive Days. He never wrote that novel, but he infused just everything he wrote or inspired with the language of the sea.

Although there are only the briefest of literal sea experiences in Dreams, the following words appear in both Dreams and in Ayers' work: fog, mist, ships, seas, boats, oceans, calms, captains, charts, first mates, storms, streams, wind, waves, anchors, barges, horizons, ports, panoramas, moorings, tides, currents, and things howling, fluttering, knotted, ragged, tangled, and murky.

My own memoir on race, Sucker Punch, offers a useful control. It makes no reference at all, metaphorical or otherwise, to any of the above words save “current” and “tides.” Yet I have spent a good chunk of every summer of my life at the ocean and many a day on a boat.

On first reading, I thought the muse had simply been careless, leaving his sea-stained fingerprints all over Obama’s memoir. On closer reading, though, the nautical imagery seems more artful than accidental. Obama, after all, sees himself as a voyager, a postmodern Odysseus. When he leaves Hawaii for college in Los Angeles, he leaves his white mother and grandparents “ at some uncharted border.” From this point on, he himself will be responsible for “charting his way through the world.”

Like Odysseus, Obama feels himself “unanchored to place.” He adds, “What I needed was a community.” Obama’s effort to locate that community in the African-American homeland, like Odysseus’s effort to regain his troubled Ithaca home, is fraught with peril and temptation, some of it factual, some of it finessed from facts, some of it fully invented.

Obama is not the first writer to see Los Angeles as the land of the lotus-eaters “Junkie. Pothead,” he writes in retrospect of the experience, “That’s where I’d been headed: the final, fatal role of the young would-be black man.”

In Los Angeles too, he seals his ears to the siren call of “green-eyed Joyce.” This is the young woman at Occidental College who had tried to lure him from his inexorable journey to black self-fulfillment with the seduction of “multiracial” anonymity. Despite her “honey skin and pouty lips,” Obama resists the “gravitational pull” of her post-racial promise.

While still in Los Angeles, Obama finds his own private Cyclops in a scene that feels largely, if not wholly, contrived. An Iranian student sitting across from Obama at the library, whom Obama describes as “older balding man with a glass eye,” chides him and a black friend about the failure of American slaves to rebel in any meaningful way.

Obama’s friend falls strangely mute before the attack, but Obama leaps to the slaves’ defense despite his lack of natural connection to their legacy. “Was the collaboration of some slaves any different than the silence of some Iranians who stood by and did nothing as Savak thugs murdered and tortured opponents of the Shah?” he asks.

This conversation allegedly takes place in the spring of 1981, just months after the release of 52 American hostages from 444 days of captivity in the newly Islamic Iran. If Obama were still focusing his anti-Iranian wrath on the Shah and Savak, he was among the handful of Americans so inclined. The implict anti-Americanism in this scene seems to be as much the inspiration of Obama’s muse as the Homeric allusion.

Obama leaves Los Angeles for Columbia later that same year. As might be expected, Manhattan proves more seductive than Hawaii or Los Angeles. Obama finds himself as attracted as he is repelled by “the beauty, the filth, the noise, and the excess” of the city. There was no denying “the city’s allure,” he writes, nor “its consequent power to corrupt.” This was Obama’s monstrous rock-based Scylla, the notorious devourer of men. Its power makes him “fearful of falling into old habits.”

While in New York, having quit his job “behind enemy lines” in a corporate office, Obama takes a contemplative detour to the East River. In front of him churns his personal Charybdis. “ You know why sometimes the river runs that way and then sometimes it goes this way?” a young black boy asks him. “It probably had to do with the tides,” Obama tells the boy, but he sees mirrored in the swirling waters of the river his own paralyzing indecision . Caught between the Charybdis of confusion and the Scylla of corruption, Obama feels himself “uncertain of my ability to steer a course of moderation.”

If this Homeric allusion is open to debate, there is no denying the muse’s hand in this passage. In Ayers’ 1993 book, To Teach, he tells a stunningly similar story about a group of students who excitedly discover the parallel spot on the Hudson, also a tidal river, where the southern flow of the river meets the northern flow of the tides. In Fugitive Days, Ayers likewise uses the phrase “behind enemy lines” to describe his band’s position in the battle against “the monster.” That monster, as Ayers describes it, is “capitalism itself, the system of imperialism.”

In Dreams, Obama writes about “white capitalist imperialism” as well. He attributes this phrase to a woman he encounters at a Stokely Carmichael speech on the Columbia campus. Whether Obama ever actually saw Carmichael is questionable. The one time “honorary prime minister” of the Black Panthers was in self-imposed exile in Guinea in the early 1980s. Ayers, however, knew Carmichael well. He had taken a class with Carmichael in the 1960’s and writes about it enthusiastically in To Teach.

It is in Manhattan too that Obama meets his Circe. “ She was white. She had dark hair, and specks of green in her eyes. Her voice sounded like a wind chime,” he would later tell his half-sister Auma. “We saw each other for almost a year.” Obama, however, came to see that he and the girl lived in “two worlds.” He sensed that “if we stayed together I’d eventually live in hers.” And so he pushes her away.

Odysseus too shared the temptress Circe’s bed for a year. Like Obama’s unnamed girlfriend, Circe lived in a “splendid house” on “spacious grounds.” She likewise wanted her lover to stay forever, but Odysseus’s mates warned him off, “You god-driven man, now the time has come to think about your native land once more, if you are fated to be saved and reach your high-roofed home and your own country.” (Ian Johnston translation)

If Obama’s friend nicely fills the Circe role, she is nonetheless grounded in the real life person of Diana Oughton. As her FBI files attest, Oughton had brown hair and green eyes. Ayers’ lover Oughton and Obama’s alleged lover shared similar family backgrounds as well. In fact, as I have detailed in these pages earlier, they seemed to have grown up on the very same estate, right down to the ancestral home, the encircling trees, and small lake in the middle.

If Obama’s friend nicely fills the Circe role, she is nonetheless grounded in the real life person of Diana Oughton. As her FBI files attest, Oughton had brown hair and green eyes. Ayers’ lover Oughton and Obama’s alleged lover shared similar family backgrounds as well. In fact, as I have detailed in these pages earlier, they seemed to have grown up on the very same estate, right down to the ancestral home, the encircling trees, and small lake in the middle.

The passage in Dreams in which Obama describes this lover, the only woman so identified in the memoir, begins with one intriguing detail. After Auma questions him about his past love, and before he answers, Obama pulls out “two green peppers, setting them on the cutting board.” To be sure, the author here takes a fair amount of poetic license. Writing this ten years after the fact, Obama would have been hard pressed to remember the conversation, let alone the food he was preparing at the time.

What intrigues about the detail is that in his 1997 book, A Kind And Just Parent, Ayers specifically links “green peppers” with “saltpeter” and other substances that scare young men with the threat of impotence. Obama’s muse would have known of Circe’s power to turn Odysseus into “ an unmanned weakling,” but the subtlety of the green peppers reference here seems somehow more personal

In any case, Obama manages to find his way to Chicago and a career as a community organizer. Obama has convinced himself that even if he were not born into African American culture, he could somehow earn his way in through good works. And good works, he reckons, offer the “promise of redemption.”

What the fatherless Obama lacks, however, is a “guide that might show me how to join this troubled world.” Even after attaching himself to the Reverend Wright’s church, he still feels the “incompleteness” of his identity as a black American. As the book is laid out, it is immediately after his first visit to Wright’s church that Obama leaves on his African pilgrimage.

His first stop is Europe. This, Obama realizes, is a “mistake.” Although beautiful, Europe wasn’t his. “I began to suspect,” writes Obama, “that my European stop was just one more means of delay, one more attempt to avoid coming to terms with the Old Man.” Like Odysseus, he knows he has to go home.

Home for Obama, however, is not exactly Africa. This he senses almost immediately. “For a span of weeks or months, you could experience the freedom that comes from not feeling watched,” Obama discovers, but that sensation does not endure. He still looks and thinks like an American.

Africa does serve a purpose, the same purpose, in fact, that Odysseus’ trip to the underworld serves, a chance to reconcile with the spirits of the past. “The Old Man’s here,” Obama thinks, “although he doesn’t say anything to me. He’s here, asking me to understand.”

Needing to consult the blind prophet Teiresias, Odysseus makes a long and difficult journey to “Hades’ murky home,” specifically a stream called Acheron, which branches off the river Styx. There, he is instructed to pour libations to the deceased. Once he does, he is swarmed by the many and sundry “shades of the dead.”

Obama makes a comparably difficult journey of several days duration by train, bus, jalopy and finally on foot to “a wide chocolate- brown river,” besides which rests the grave of Obama’s great-great grandfather in the heart of “ Obama Land.” Here, Obama meets, among other relatives, a blind great uncle who pours him his own home brewed libation. The night passes for Obama as in a dream. Men come and go, drinking “ceremoniously,” perhaps six men, perhaps ten. Obama is not quite sure. They “merge with the shadows of corn.”

Among the friends and relations that Odysseus meets is Agamemnon. Having been betrayed by his own wife, he warns his friend of the dangers that women pose. “That’s why you should never treat them kindly,” he says, “not even your own wife.”

A cousin freely gives Obama similar advice. “I swear, bwana, marriage takes you,” he tells Obama. “Of course, there are limits to what a man should take. My wife knows not to cross me too often.”

If the blind seer Teiresias gives Odysseus involved instructions on how to return home, Obama’s great uncle cuts to the chase. He tells Obama that many men have been lost to the “white man’s country,” including his own son. “Such men are like ghosts,” he says, adding that if Obama hears of his son, “You should tell him that he should come home.” Obama leaves the land of his ancestors wiser than when he came, his great uncle’s “blind eyes staring out into the darkness.” He knows that he has to go home too.

What Obama pulls from his African experience, in a sequence that feels heavily indebted to his muse and largely contrived after the fact, is that home is where the heart is. Cultural “authenticity” is an illusion, and there is “no shame in confusion.” There was only shame in the silence that leads the individual to try to form his identity—to become authentically himself--without help from others.

From Africa, the book passes at warp speed through Obama’s Harvard experience and culminates with his wedding to Michelle. As with all previous relationships, this tale of courtship is strikingly devoid of any reference to love, sex, or romance. At his most passionate, Obama says of Michelle that “in her eminent practicality and midwestern (sic) attitudes, she reminds me not a little of Toot [his grandmother].” That description must have warmed Michelle’s heart.

More important to Obama is that Michelle is “a daughter of the South Side,” an instinctive African American, one descended from slaves. Just as the Odyssey ends with Odysseus reuniting with his wife, Penelope, Obama rounds his circle by marrying into the culture that has eluded him all his life. With the promise of fatherhood implicit in marriage, the abandoned son claims the potential to be a father and the father of authentic African Americans at that.

In completing this journey, Obama explores any number of Ayers’ themes, including the unreliability of the narrator, the need for intimacy, the interiority of the struggle, and the convergence of the individual with the universal. Both writers use the very same terms in describing the “fictions” into which people force their lives, the “grooves” into which they fall, the “poses” they assume, the “narratives” they “construct,” the “messy” condition of their “reality,” and even the “stitched together” nature of their identities. This is not coincidence.

On a final note, the penultimate paragraph of the book has Obama describing his older brother Roy, who now calls himself “Abongo.” The alert reader hears in this description, especially its first sentence, a mischievous muse describing Obama:

The words he speaks are not fully his own, and in his transition he can sometimes sound stilted and dogmatic. But the magic of his laughter remains, and we can disagree without rancor.

His conversion has given him solid ground to stand on, a pride in his place in the world. From that base I see his confidence building; he begins to venture out and ask harder questions; he starts to slough off the formulas and slogans and decides what works best for him.

He can’t help himself in this process, for his heart is too generous and full of good humor, his attitude toward people too gentle and forgiving, to find simple solutions to the puzzle of being a black man.

Mischievous indeed!

Editor's note: For a more complete account of this phenomenon, read Jack Cashill's amazing new book, "Hoodwinked: How Intellectual Hucksters Have Hijacked American Culture.