Bonds' Home Run Quest

Exposes Left Coast Ethics

California, What's

the Matter with

© Jack Cashill

WorldNetDaily.com -

These next days or weeks, as Barry Bonds proceeds in his unseemly quest to break Hank Aaron’s all-time home run record, scores of thousands of the Bay Area’s best citizens will pay as much as $85 a game to watch a spectacle that one Justice Department spokesman rightly describes as “cheating the baseball immortals.”

Indeed, what makes this story worth telling at all is the Bay Area embrace of Barry Bonds, an embrace that explains all too much about the casual ethics of the contemporary left.

Barry himself is one a kind. The son of Giants’ star Bobby Bonds,

Barry started nursing career-long sulk at Junipero Serra High in San Mateo, known locally as “the jock school to end all jock schools.” Although the school’s mission was to “foster Gospel values,” those values apparently did not include humility, at least in Bond’s case. By the time major league scouts came sniffing, one of them would sum up the consensus on Barry’s “Attitude/ Personality” with one highly explanatory word, “asshole.” In Pittsburgh, at his first major league stop, the writers gave him their MDP—“most despised player”--award. In San Francisco, where he returned in 1993 as a two time MVP, he continued to creep out teammates and fans at a Hall of Fame level.

Unlike his future co-conspirator, Victor Conte lived a textbook Left Coast life. Born in Fresno to a working class Catholic Italian family, Victor dropped out of the local community college right after the Manson killings and just before Altamont to join a rock group called “Common Ground.” Ten years later, his father would still be introducing him thusly, “This is my son Victor. He’s never worked a day in his life.”

Always a charmer and a hustler, Victor joined a new band in 1970. The deep irony of its name would escape Victor for another thirty years, “Pure Food and Drug Act.” On the road in 1970’s California, Victor quickly shucked his family’s Catholicism and began studying Eastern philosophy, particularly the Bhagavad Vita. If this sacred Hindu scripture contained any “Thou Shalt Nots,” Conte must have overlooked them.

In 1977, Conte arrived. He got married and joined a major funk band, Tower of Power, at the peak of its success. His constant scheming, however, got him dumped within a year or two. He and wife Audrey bounced around for the next few years in classic New Age fashion, practicing yoga, eating organic foods, and going on pseudo-religious retreats. In the midst of all this healthy living, Conte found time to deal drugs and Audrey found time to get addicted. When they split in 1995, that addiction would cost Audrey custody of the couple’s three daughters.

Before that unfortunate turn of events, Conte and Audrey had opened a place called the Millbrae Holistic Health Center, just about fifteen minutes north of San Carlos where Barry Bonds had grown up. Conte dealt vitamins at the store and pot from the house. The up and coming young drug dealer used the Health Center as a springboard to his next big idea, sports medicine, and soon after launched a new venture called the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative, BALCO for short. From his humble BALCO offices, located in a strip mall near the San Francisco airport, Conte dispensed all manner of illegal performance enhancing drugs to all kinds of athletes.

San Francisco Chronicle reporters Lance Williams and Mark Fainaru-Wada tell the BALCO story well and in detail in their 2006 book, Game of Shadows. Suffice it to say that Bonds began using steroids as a 34 year-old before the 1999 season. Conte and Bonds hooked up two years later, ten years after the Federal Government had outlawed the non-prescription use of steroids. That year Bonds hit a major-league record 73 home runs and won the Most Valuable Player Award for the National League. Major League Baseball banned steroid use in 2002, but with Conte’s all but undetectable drugs Bonds felt free to ignore the ban. He would win the MVP award in 2002, 2003, and 2004 as well.

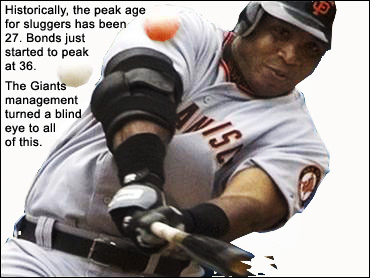

Bond’s stats bewildered baseball historian Bill Jenkinson, who has made a science of analyzing home run hitting. Not only was Bonds hitting more home runs as he moved into his late thirties, but he was also hitting them much farther. “This is not humanly possible,” says Jenkinson. “It cannot be done by even the most amazing athletic specimen of all time . . . unless that specimen is cheating.” In the 12 years before that specimen started using steroids, 1986-1998, he had averaged 32 home runs a season. In his five full seasons of steroid use, Bonds averaged 52 homers. In 2006, his first full post-steroid season, Bonds hit 26 home runs. Do the math. Historically, the peak age for sluggers has been 27. Bonds just started to peak at 36. The Giants management turned a blind eye to all of this.

Conte had put Bonds in the record books. And there’s the rub. Baseball is a game of records, of traditions. Unlike, say, bodybuilding, baseball has meaning only in direct reference to its history. Who knows or cares what amazing hulk won the Mr. Olympia Contest from 1970-1974? Everyone in that world took steroids. Even if the winner did become the governator, he did not cheat his sport the way Bonds has. Bonds has been undermining not just the integrity of the game as played today, but the very meaning of the sport, past, present, and future. He has messed with history the way Bill and Ted and other excellent movie adventurers have. So toxic are his post-steroid statistics, in fact, that Major League Baseball may have to declare them a Superfund site and expunge them.

As Bonds lumbered shamelessly on towards Hank Aaron’s all time home run record, he continued to cheat, and the San Francisco fans continued to cheer. This should not surprise. History and tradition--of anything other than San Francisco itself--matter less in the Bay Area than they do anywhere in America. Even after the Feds busted Conte and dragged a dissembling Bonds before a grand jury, Giant fans exalted in the team’s performance. “The man is a saint,” gushed a kindergarten teacher with her young son at SBC on the occasion of his 700 th home run. After his grand jury appearance, notes Jeff Pearlman in his Bonds bio, Love Me, Hate Me, “ San Francisco fans hailed their star not only as a hero but as a martyr.”

By the end of the 2005 season even die-hard San Francisco fans had to acknowledge that Bonds had scammed his way to his stats. In a random ballpark survey, 92 out of 100 Giant fans conceded that Bonds had cheated. Still, only 24 out of 100 expressed any concern that this might be wrong. The email Williams and Fainaru-Wada received from their Chronicle readers was just as whacked. They “passionately insisted they didn’t care,” but that did not deter them from attacking the pair for reporting the truth. Among the fans weighing in against these “so-called journalists” was former mayor, Willie Brown.

When I talked to Lance Williams in mid-season 2006, he found the fan response to be the most revealing element in the whole saga. Despite their presumed ethical superiority, Bay Area fans showed little regard for the character of the man and even less for the integrity of the game.

Maybe more than most would care to admit. As Pearlman wryly observes, “ San Francisco led the league in pre-game ceremonies to bring attention to world problems.” And yet as steroid abuse swelled nationwide, the organization ignored a problem that was potentially lethal and altogether local. Worse, the Giants held up as a model for young San Franciscans a man whose own abuse, if emulated, could turn their heads into pumpkins and their testicles into peas.

A 12 year-old fan, interviewed by the Chronicle in July 2006, perfectly mimics the smugly amoral drift of Bay Area opinion. "I'm just glad he's not in prison," said the boy relieved that Bonds was not to be charged with perjury, "It's pretty much all racist. They keep trying to get him, but he's never failed a drug test. They don't have anything on him. They're just going to keep trying until they do." The boy, no more deprived than Bonds himself, had flown in to San Francisco to catch a four game series with his parents. His racial hauteur was impressive even by Bay Area standards.

As to Conte, he went to jail unrepentant, threatening to write an autobiography called, No Choice, its premise being that if everyone cheats you have no choice but to cheat too--and the fans, presumably, have no choice but to cheer the cheats. In the Bay Area, this all passes for wisdom.

Cashill’s new book, What’s the Matter with California, will be out in October.